Nigeria is the top African Exporter of students

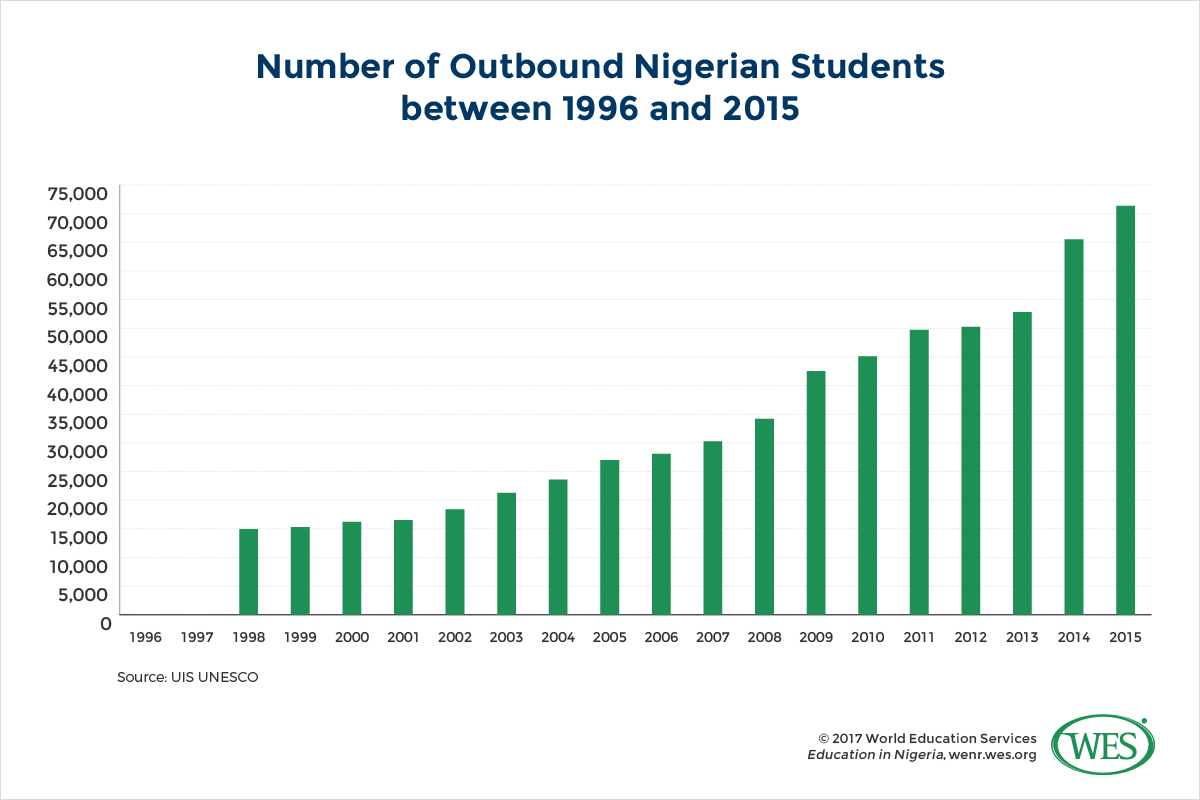

Nigeria is the number one country of origin for international students from Africa: It sends the most students overseas of any country on the African continent, and outbound mobility numbers are growing at a rapid pace. According to data from the UNESCO Institute of Statistics (UIS), the number of Nigerian students abroad increased by 164 percent in the decade between 2005 and 2015 alone– from 26,997 to 71,351.

Nigeria is the number one country of origin for international students from Africa: It sends the most students overseas of any country on the African continent, and outbound mobility numbers are growing at a rapid pace. According to data from the UNESCO Institute of Statistics (UIS), the number of Nigerian students abroad increased by 164 percent in the decade between 2005 and 2015 alone– from 26,997 to 71,351.

In the short term, Nigeria’s oil

price-induced fiscal crisis is likely to affect outbound student mobility.

As many as 40 percent of Nigerian overseas students are said to

rely on scholarships, many of which were backed by oil and gas revenues. The

vast majority of these scholarships have been scaled back or scrapped

altogether in the wake of the fiscal crisis. Further exacerbating the immediate

prospects of Nigeria’s overseas students was a 2016 crash of the foreign

exchange rate of Nigeria’s currency, the naira. The crash increased costs for

international students, and reportedly left large numbers of Nigerian overseas

students unable to make tuition payments.

But for all the short term upheaval, the push factors that underlie the outflow

of students in Nigeria are fundamentally unchanged. These include:

The failure of Nigeria’s education system to meet booming demand

The often poor quality of its universities

Rapid growth in the number of middle class families who can afford to send

their children overseas

Given those drivers, it seems unlikely that the crisis will lead to a sharp and

prolonged downturn of international student numbers.

Destination Countries

Due to colonial ties and a shared language, the United Kingdom has long been

the favorite destination for Nigerian students overseas with numbers booming in

recent years. Some 17,973 Nigerian students studied in the UK in 2015 .

In line with a general shift towards regionalization in African student

mobility, Nigerian students in recent years have been increasingly studying in

countries on the African continent itself. Ghana has recently overtaken the

U.S. as the second-most popular destination country, attracting 13,919 Nigerian

students in 2015, according to the data provided by the UNESCO

Institute of Statistics (UIS).

Despite this repositioning, the U.S. remains a highly popular study

destination. Nigerian enrollments in U.S. institutions have been

increasing slowly but steadily over the past 15 years from 3,820 in 2000/01 to

10,674 in 2015/16, according to the Open Doors data provided by the Institute of

International Education (IIE). Nigerian students are currently the 14th largest

group among foreign students in the United States, and contributed an estimated

USD $324 million to the U.S. economy in 2015/16. Engineering, business,

physical sciences, and health-related fields continually rank as the most

popular fields of study among Nigerian students enrolled at U.S. universities.

Another country that has more recently emerged as a popular destination for

Nigerians, especially among those from the Muslim north, is Malaysia. Aside

from the appeal of Malaysia as a majority Islamic country, low tuition and

living costs are attractive, as is the opportunity to earn a prestigious

Western degree from one of the several foreign branch campuses that operate in

the country. As per UIS, 4,943 Nigerians were studying in Malaysia in 2015,

making the country the fourth most popular destination country of Nigerian

students. Another Muslim country that is increasingly attracting Nigerian

students is Saudi Arabia, which in 2015 hosted 1,915 students from Nigeria.

IN BRIEF: THE EDUCATION SYSTEM

Administration

Nigeria has a federal system of government with 36 states and the Federal

Capital Territory of Abuja. Within the states, there are 744 local governments

in total.

Education is administered by the federal, state and local governments. The

Federal Ministry of Education is responsible for overall policy formation and

ensuring quality control, but is primarily involved with tertiary education.

School education is largely the responsibility of state (secondary) and local

(elementary) governments.

The country is multilingual, and home to more than 250 different ethnic groups.

The languages of the three largest groups, the Yoruba, the Ibo, and the Hausa,

are the language of instruction in the earliest years of basic instruction;

they are replaced by English in Grade 4.

Overall Structure

Nigeria’s education system encompasses three different sectors: basic education

(nine years), post-basic/senior secondary education (three years), and tertiary

education (four to six years, depending on the program of study).

According to Nigeria’s latest National Policy on Education (2004), basic

education covers nine years of formal (compulsory) schooling consisting of six

years of elementary and three years of junior secondary education. Post-basic

education includes three years of senior secondary education.

At the tertiary level, the system consists of a university sector and a

non-university sector. The latter is composed of polytechnics, monotechnics,

and colleges of education. The tertiary sector as a whole offers opportunities

for undergraduate, graduate, and vocational and technical education.

The academic year typically runs from September to July. Most

universities use a semester system of 18 – 20 weeks. Others run

from January to December, divided into 3 terms of 10 -12 weeks.

Basic Education

Elementary education covers grades one through six. As per the most

recent Universal

Basic Education guidelines implemented in 2014, the curriculum

includes: English, Mathematics, Nigerian language, basic science and

technology, religion and national values, and cultural and creative arts,

Arabic language (optional). Pre-vocational studies (home economics,

agriculture, and entrepreneurship) and French language are introduced in grade

4.

Nigeria’s national policy on education stipulates that

the language of instruction for the first three years should be the

“indigenous language of the child or the language of his/her immediate

environment”, most commonly Hausa, Ibo, or Yoruba. This policy may,

however, not always be followed at schools throughout the country, and

instruction may instead be delivered in English. English is commonly the

language of instruction for the last three years of elementary school. Students

are awarded the Primary School Leaving Certificate on completion of

Grade 6, based on continuous assessment.

Progression to junior secondary education is automatic and compulsory. It lasts

three years and covers grades seven through nine, completing the basic stage of

education. The curriculum includes the same subjects as the elementary stage,

but adds the subject of business studies.

At the end of grade 9, pupils are awarded the Basic Education Certificate (BEC),

also known as Junior School Certificate, based on their performance in

final examinations administered by Nigeria’s state governments. The BEC

examinations take place nationwide in June each year and usually last for a

week. Students are expected to take a minimum of ten subjects and a maximum of

thirteen. Students must achieve passes in six subjects, including English

and mathematics, to pass the Basic Education Certificate Examination.

Crisis in Elementary Schooling

Like the country’s education system as a whole, Nigeria’s basic education

sector is overburdened by strong population growth. A full 44 percent of the country’s population was below the

age of 15 in 2015, and the system fails to integrate large parts of this

burgeoning youth population. According to the United Nations, 8.73

million elementary school-aged children in 2010 did not participate in

education at all, making Nigeria the country with the highest number of

out-of-school children in the world.

The lack of adequate education for its children weakens the Nigerian system at

its foundation. To address the problem, thousands of new schools have been

built in recent years. The Nigerian government has the official goal to

universalize free basic education for all children. Yet, despite recent

improvements in total enrollment numbers in elementary schools, the basic

education system remains underfunded; facilities are often poor, teachers

inadequately trained, and participation rates are low by international

standards.

In 2010, the net enrollment rate at the elementary level was 63.8 percent compared to a global average of

88.8 percent. According to recent statistics on completion rates, approximately one-quarter of current

pupils drop out of elementary school. These low participation rates perpetuate

illiteracy rates in Nigeria, which, while relatively high compared to other

Sub-Saharan countries, are well below the global average. The country in 2015

had a youth literacy rate of 72.8 percent and an adult literacy rate of 59.6

percent compared to global rates of 90.6 percent (2010) and 85.3 percent

(201o), respectively (data reported by the World

Bank). Within Nigeria, there is a distinct regional difference in

participation rates in education between the oil-rich South and the

impoverished North of the country, in some parts of which elementary enrollment

rates were reportedly below 25 percent in 2010.[3]

Senior Secondary Education

Senior Secondary Education lasts three years and covers grades 10 through 12.

In 2010, Nigeria reportedly had a total 7,104 secondary schools with 4,448,981

pupils and a teacher to pupil ratio of about 32:1.[4]

Reforms implemented in 2014 have led to a restructuring of the national curriculum. Students are currently required to

study four compulsory “cross-cutting” core subjects, and to choose additional

electives in four available areas of concentration. Compulsory subjects are:

English language, mathematics, civic education, and one trade/entrepreneurship

subject. The available concentration subjects are Humanities, science and

mathematics, technology, and business studies. The new curriculum has a

stronger focus on vocational training than previous curricula and is intended

to increase the employability of high school graduates in light of high youth

unemployment in Nigeria.

In addition to public schools, there are a large number of private secondary

schools, most of them expensive and located in urban centers. Many private

schools include U.S. K-12, International Baccalaureate or Cambridge International

Examination curricula, allowing students to take international

examinations like the International General Certificate of Secondary

Education (IGSCE) during their final year in high school.

Senior School Certificate Examination

At the end of the 12th grade in May/June, students sit for the Senior

School Certificate Examination (SSCE). They are examined in a minimum of

seven and a maximum of nine subjects, including mathematics and English, which

are mandatory. Successful candidates are awarded the Senior Secondary

Certificate (SSC), which lists all subjects successfully taken. Students

can sit for a second SSC annual exam if interested or if they need to improve

on poor results in the May/June exams. [5]

SSC examinations are offered by two different examination boards: the West African Examination

Council and the National

Examination Council (NECO). The examination is open to students

currently enrolled in the final year of secondary school, as well external

private candidates (in the November/December session only). The SSCE grading

scale is as follows for both WAEC and NECO administered examinations:

Admission to public universities in Nigeria is competitive and based on scores

obtained in the Unified Tertiary Matriculation Examination as well as the

SSC results. (The Unified Tertiary Matriculation Examination is discussed in

greater detail below.) Most universities require passes in at least five SSC

subjects and take into consideration the average score. Students must score an

average grade of at least ‘credit’ level (C6) or better to be considered for

admission to public universities; some institutions may require higher grades.

It is possible to access student results through the West African Examinations

Council (WAEC)/or National Examination Council (NECO) websites. The student

must provide the PIN number that they purchase for the equivalent of

approximately USD $3 (available at banks, WAEC regional offices and online).

With the PIN number, it is possible to retrieve a printable copy of the WAEC

results. This is the fastest and most reliable way of verifying a student’s

results from Nigeria.

Vocational and Technical Education

The Nigerian education system offers a variety of options for vocational and

technical education at both the secondary and post-secondary levels. To

combat chronic youth unemployment, the Federal Ministry of Education presently

supports a number of reform projects to advance vocational training, including

the “vocationalization” of secondary education and the

development of a National Vocational Qualifications Framework by the

National Board for Technical Education, similar to the qualifications

frameworks found in other British Commonwealth countries.

A two-tier system of nationally certified programs is offered at science

technical schools, leading to the award of National Technical/Commercial

Certificates (NTC/NCC)and Advanced National Technical/Business

Certificates. The lower-level program lasts three years after Junior Secondary

School and is considered by the Joint Admission and Matriculation Board as

equivalent to the SSC.

The advanced program requires two years of pre-entry industrial work experience

and one year of full-time study in addition to the NTT/NCC. All certificates

are awarded by the National

Business and Technical Examinations Board (NABTEB).

Another type of – relatively new – vocational training institution is the

so-called “Vocational Enterprise Institutions” (VEIs) and “Innovation

Enterprise Institutions” (IEIs), established to provide employment-geared

education in the private sector. At the secondary level, VEIs offer

programs for graduates of junior secondary school leading to a National

Vocational Certificate (NVC). Programs are between one and three

years in length and conclude with the award of the NVC Part 1, Part 2 and

Final.

At the post-secondary level, IEIs offer diploma programs for holders of the

SSC. Programs are two years in length (3-4 years part-time) and lead to the

so-called National Innovation Diploma. As of 2017, there were 137 approved

IIEs and 72 approved VEIs listed on the website of the National Board

for Technical Education.

University Admissions

Until the 1970s, Nigerian universities set their own admissions standards. Due

to the growing number of universities in Nigeria’s sprawling higher education

system, this practice became problematic, and, in 1978, the Nigerian government

established the Joint

Admissions and Matriculation Board (JAMB) to oversee a centralized

admissions test called the Unified Tertiary Matriculation Examinations (UTME).

The fiscal crisis of the Nigerian government has recently led to

discussions about abolishing the JAMB as a cost-cutting measure. In November

of 2016, the JAMB announced that it did no longer have adequate funds to

effectively conduct the nation-wide UTME. Despite these financial difficulties,

all public universities are presently mandated to use the governmental

admissions test in their admissions decisions, even though some universities

have additional requirements going beyond the UTME.

The Unified Tertiary Matriculation Examination (UTME) is a

computerized standard test. The multiple-choice test is three hours in duration

and conducted once a year, typically in March. It can be taken at test

centers in each state of the Nigerian federation, as well as some overseas

testing facilities.

The UTME is open to students who achieve credit level or better in English and

four other subjects in the SSC exams at the end of the senior secondary cycle.

Students with equivalent qualifications like the National Technical Certificate

may also be admitted.

Students who sit for the UTME must take exams in English and three subjects

related to their intended major in order to be considered for admission into

universities. A total of 23 different UTME subject combinations are offered in

the fields of: Banking and finance, law, English and literary studies, mass

communication, linguistics, philosophy, engineering, medicine and surgery,

computer science, nursing, pharmacy, biochemistry, industrial chemistry,

geology, mathematics, microbiology, economics, sociology, psychology, political

science, public administration, and accounting and business administration.

Test takers can achieve a maximum score of 400. Most universities require a

minimum score between 180 and 200, although high-demand universities or

programs may require higher scores.

Many universities also conduct additional screening or post-UTME examinations

before a final admission decision is made. These post-UTME requirements can be

demanding and are often reported to be a source of frustration for Nigeria’s

university applicants. In 2016, the JAMB announced a number of reforms,

including stopping universities from using written post-UTME

exams, as well as changes to the UTME scoring system. As of February 2017, the

status of the reforms was unclear, due to resistance from universities. Many

universities continued to use post-UTME exams in the fall 2016 admissions

cycle.

When registering with JAMB for the UTME, each student can apply to up to six

institutions: two universities, two polytechnics, and two colleges of

education, with first and second choice programs for each institution type. A

number of universities accept applications for post-UTME admissions screening

from students that that did not get into their universities of choice.

Some private institutions accept applicants that did not sit for the UTME at

all.

Not Enough University Seats

According to the statistics JAMB provides on its website, a

total of 1.579,027 students sat for the UTME exam in 2016. 69.6 percent of

university applications were made to federal universities, 27.5 percent to

state universities, and less than 1 percent to private universities. The number

of applicants currently exceeds the number of available university seats by a

ratio of two to one. In 2015, only 415.500 out of 1.428,379 applicants were

admitted to a university, according to the data provided by JAMB.

This admission ratio, low as it may be, is a significant improvement versus 10

years ago when the ratio was closer to one in ten for university entry. But the

admissions crisis continues to be one of Nigeria’s biggest challenges in higher

education, especially given the strong growth of its youth population.

Nigeria’s system of education presently leaves over a million qualified

college-age Nigerians without access to postsecondary education on an annual

basis.

High unemployment among university graduates is also a major problem but does

not appear to be a deterrent to those seeking admission into institutions of

higher learning. In 2016, the online magazine Quartz reported that a staggering

47 percent of Nigerian university graduates were without employment, based on a

survey of 90,000 Nigerians.

TERTIARY EDUCATION: AN OVERVIEW

UNIVERSITIES

The National University Commission (NUC), the government umbrella organization

that oversees the administration of higher education in Nigeria, listed 4o

federal universities, 44 state universities, and 68 private universities as

accredited degree-granting institutions on its website as of 2017.

Many of these institutions are relatively new. In response to demographic

pressures, Nigeria’s higher education sector expanded over a relatively short

period. In 1948, there was only one university-level institution in the

country, the University College of Ibadan, which was originally an affiliate of

the University of London. By 1962, the number of federal universities had

increased to five: the University of Ibadan, the University of Ife, the

University of Nigeria, Ahmadu Bello University, and the University of Lagos.

Between 1980 and 2017, the number of recognized universities has grown tenfold

from 16 to 152, as reported by Nigeria’s National Universities Commission.[6]For the first

few decades of growth, higher education capacity building was primarily in the

public sector, driven by Federal and State governments. More dramatic growth

occurred beginning in the late 1990s when the Nigerian government began to

encourage the establishment of private universities. Since then, private

institutions, which constitute some 45 percent of all Nigerian universities as

of 2017, have proliferated at a rapid pace, from 3 in 1999 to 68 in 2017. About

two-thirds of these institutions are estimated to be religiously affiliated schools.

Despite the sheer number of private institutions that have opened, enrollments

seem to be relatively low. Although estimates are difficult to find, the small

number of United Tertiary Matriculation Examination (UTME) applications

to private universities indicate that private universities account for only a

small percentage of Nigeria’s total tertiary enrollment, which UIS reported as

1,513, 371 as of 2011.[7] Covenant University, Nigeria’s largest private

university reportedly had a total enrollment of 6,822 students in

2010/2011.

Nigeria’s 40 federal universities, as well as dozens of teaching hospitals and

colleges, are under the direct purview of the NUC. State governments have

responsibility for the administration and financing of the 44 state

universities.

In addition to granting institutional accreditation, the NUC approves and

accredits all university programs. Accreditation is granted for an initial

three-year period and subsequent five-year periods. (For a detailed overview of

the process see the NUCs 2012 accreditation manual). The suspension of

accreditation for programs is not uncommon. In 2016, for example, the NUC

publicized a list of 150 unaccredited degree programs at 37 universities.

COLLEGES AND POLYTECHNICS

In addition to universities, there are a large number of polytechnics and

colleges under the purview of the National Board of Technical Education (NBTE), the

federal government body tasked with overseeing technical and vocational

education. In 2017, the NBTE recognized 107 polytechnics, 27 monotechnics, and

220 colleges in various specific disciplines. These institutions were

established to train students for technical and mid-level employment.

The National

Commission for Colleges of Education is the federal body dedicated to

overseeing non-university teacher education. As of 2017, there were 84 teacher

training colleges in Nigeria.

culled from: wes.org

But for all the short term upheaval, the push factors that underlie the outflow of students in Nigeria are fundamentally unchanged. These include:

The failure of Nigeria’s education system to meet booming demand

The often poor quality of its universities

Rapid growth in the number of middle class families who can afford to send their children overseas

Given those drivers, it seems unlikely that the crisis will lead to a sharp and prolonged downturn of international student numbers.

Destination Countries

Due to colonial ties and a shared language, the United Kingdom has long been the favorite destination for Nigerian students overseas with numbers booming in recent years. Some 17,973 Nigerian students studied in the UK in 2015 .

In line with a general shift towards regionalization in African student mobility, Nigerian students in recent years have been increasingly studying in countries on the African continent itself. Ghana has recently overtaken the U.S. as the second-most popular destination country, attracting 13,919 Nigerian students in 2015, according to the data provided by the UNESCO Institute of Statistics (UIS).

Despite this repositioning, the U.S. remains a highly popular study destination. Nigerian enrollments in U.S. institutions have been increasing slowly but steadily over the past 15 years from 3,820 in 2000/01 to 10,674 in 2015/16, according to the Open Doors data provided by the Institute of International Education (IIE). Nigerian students are currently the 14th largest group among foreign students in the United States, and contributed an estimated USD $324 million to the U.S. economy in 2015/16. Engineering, business, physical sciences, and health-related fields continually rank as the most popular fields of study among Nigerian students enrolled at U.S. universities.

Another country that has more recently emerged as a popular destination for Nigerians, especially among those from the Muslim north, is Malaysia. Aside from the appeal of Malaysia as a majority Islamic country, low tuition and living costs are attractive, as is the opportunity to earn a prestigious Western degree from one of the several foreign branch campuses that operate in the country. As per UIS, 4,943 Nigerians were studying in Malaysia in 2015, making the country the fourth most popular destination country of Nigerian students. Another Muslim country that is increasingly attracting Nigerian students is Saudi Arabia, which in 2015 hosted 1,915 students from Nigeria.

IN BRIEF: THE EDUCATION SYSTEM

Administration

Nigeria has a federal system of government with 36 states and the Federal Capital Territory of Abuja. Within the states, there are 744 local governments in total.

Education is administered by the federal, state and local governments. The Federal Ministry of Education is responsible for overall policy formation and ensuring quality control, but is primarily involved with tertiary education. School education is largely the responsibility of state (secondary) and local (elementary) governments.

The country is multilingual, and home to more than 250 different ethnic groups. The languages of the three largest groups, the Yoruba, the Ibo, and the Hausa, are the language of instruction in the earliest years of basic instruction; they are replaced by English in Grade 4.

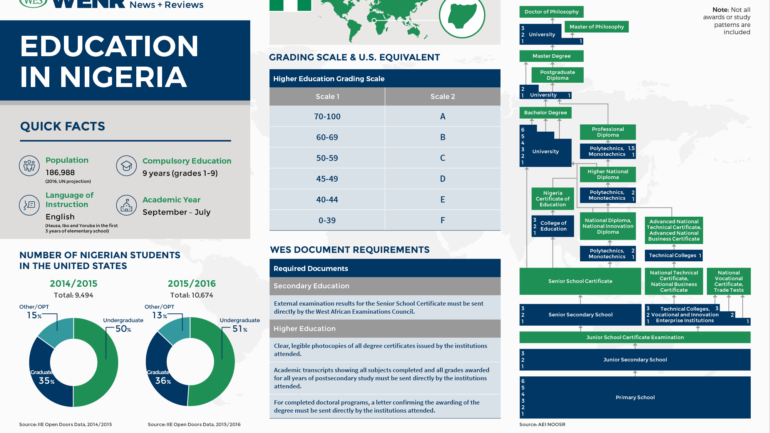

Overall Structure

Nigeria’s education system encompasses three different sectors: basic education (nine years), post-basic/senior secondary education (three years), and tertiary education (four to six years, depending on the program of study).

According to Nigeria’s latest National Policy on Education (2004), basic education covers nine years of formal (compulsory) schooling consisting of six years of elementary and three years of junior secondary education. Post-basic education includes three years of senior secondary education.

At the tertiary level, the system consists of a university sector and a non-university sector. The latter is composed of polytechnics, monotechnics, and colleges of education. The tertiary sector as a whole offers opportunities for undergraduate, graduate, and vocational and technical education.

The academic year typically runs from September to July. Most universities use a semester system of 18 – 20 weeks. Others run from January to December, divided into 3 terms of 10 -12 weeks.

Basic Education

Elementary education covers grades one through six. As per the most recent Universal Basic Education guidelines implemented in 2014, the curriculum includes: English, Mathematics, Nigerian language, basic science and technology, religion and national values, and cultural and creative arts, Arabic language (optional). Pre-vocational studies (home economics, agriculture, and entrepreneurship) and French language are introduced in grade 4.

Nigeria’s national policy on education stipulates that the language of instruction for the first three years should be the “indigenous language of the child or the language of his/her immediate environment”, most commonly Hausa, Ibo, or Yoruba. This policy may, however, not always be followed at schools throughout the country, and instruction may instead be delivered in English. English is commonly the language of instruction for the last three years of elementary school. Students are awarded the Primary School Leaving Certificate on completion of Grade 6, based on continuous assessment.

Progression to junior secondary education is automatic and compulsory. It lasts three years and covers grades seven through nine, completing the basic stage of education. The curriculum includes the same subjects as the elementary stage, but adds the subject of business studies.

At the end of grade 9, pupils are awarded the Basic Education Certificate (BEC), also known as Junior School Certificate, based on their performance in final examinations administered by Nigeria’s state governments. The BEC examinations take place nationwide in June each year and usually last for a week. Students are expected to take a minimum of ten subjects and a maximum of thirteen. Students must achieve passes in six subjects, including English and mathematics, to pass the Basic Education Certificate Examination.

Crisis in Elementary Schooling

Like the country’s education system as a whole, Nigeria’s basic education sector is overburdened by strong population growth. A full 44 percent of the country’s population was below the age of 15 in 2015, and the system fails to integrate large parts of this burgeoning youth population. According to the United Nations, 8.73 million elementary school-aged children in 2010 did not participate in education at all, making Nigeria the country with the highest number of out-of-school children in the world.

The lack of adequate education for its children weakens the Nigerian system at its foundation. To address the problem, thousands of new schools have been built in recent years. The Nigerian government has the official goal to universalize free basic education for all children. Yet, despite recent improvements in total enrollment numbers in elementary schools, the basic education system remains underfunded; facilities are often poor, teachers inadequately trained, and participation rates are low by international standards.

In 2010, the net enrollment rate at the elementary level was 63.8 percent compared to a global average of 88.8 percent. According to recent statistics on completion rates, approximately one-quarter of current pupils drop out of elementary school. These low participation rates perpetuate illiteracy rates in Nigeria, which, while relatively high compared to other Sub-Saharan countries, are well below the global average. The country in 2015 had a youth literacy rate of 72.8 percent and an adult literacy rate of 59.6 percent compared to global rates of 90.6 percent (2010) and 85.3 percent (201o), respectively (data reported by the World Bank). Within Nigeria, there is a distinct regional difference in participation rates in education between the oil-rich South and the impoverished North of the country, in some parts of which elementary enrollment rates were reportedly below 25 percent in 2010.[3]

Senior Secondary Education

Senior Secondary Education lasts three years and covers grades 10 through 12. In 2010, Nigeria reportedly had a total 7,104 secondary schools with 4,448,981 pupils and a teacher to pupil ratio of about 32:1.[4]

Reforms implemented in 2014 have led to a restructuring of the national curriculum. Students are currently required to study four compulsory “cross-cutting” core subjects, and to choose additional electives in four available areas of concentration. Compulsory subjects are: English language, mathematics, civic education, and one trade/entrepreneurship subject. The available concentration subjects are Humanities, science and mathematics, technology, and business studies. The new curriculum has a stronger focus on vocational training than previous curricula and is intended to increase the employability of high school graduates in light of high youth unemployment in Nigeria.

In addition to public schools, there are a large number of private secondary schools, most of them expensive and located in urban centers. Many private schools include U.S. K-12, International Baccalaureate or Cambridge International Examination curricula, allowing students to take international examinations like the International General Certificate of Secondary Education (IGSCE) during their final year in high school.

Senior School Certificate Examination

At the end of the 12th grade in May/June, students sit for the Senior School Certificate Examination (SSCE). They are examined in a minimum of seven and a maximum of nine subjects, including mathematics and English, which are mandatory. Successful candidates are awarded the Senior Secondary Certificate (SSC), which lists all subjects successfully taken. Students can sit for a second SSC annual exam if interested or if they need to improve on poor results in the May/June exams. [5]

SSC examinations are offered by two different examination boards: the West African Examination Council and the National Examination Council (NECO). The examination is open to students currently enrolled in the final year of secondary school, as well external private candidates (in the November/December session only). The SSCE grading scale is as follows for both WAEC and NECO administered examinations:

Admission to public universities in Nigeria is competitive and based on scores obtained in the Unified Tertiary Matriculation Examination as well as the SSC results. (The Unified Tertiary Matriculation Examination is discussed in greater detail below.) Most universities require passes in at least five SSC subjects and take into consideration the average score. Students must score an average grade of at least ‘credit’ level (C6) or better to be considered for admission to public universities; some institutions may require higher grades.

It is possible to access student results through the West African Examinations Council (WAEC)/or National Examination Council (NECO) websites. The student must provide the PIN number that they purchase for the equivalent of approximately USD $3 (available at banks, WAEC regional offices and online). With the PIN number, it is possible to retrieve a printable copy of the WAEC results. This is the fastest and most reliable way of verifying a student’s results from Nigeria.

Vocational and Technical Education

The Nigerian education system offers a variety of options for vocational and technical education at both the secondary and post-secondary levels. To combat chronic youth unemployment, the Federal Ministry of Education presently supports a number of reform projects to advance vocational training, including the “vocationalization” of secondary education and the development of a National Vocational Qualifications Framework by the National Board for Technical Education, similar to the qualifications frameworks found in other British Commonwealth countries.

A two-tier system of nationally certified programs is offered at science technical schools, leading to the award of National Technical/Commercial Certificates (NTC/NCC)and Advanced National Technical/Business Certificates. The lower-level program lasts three years after Junior Secondary School and is considered by the Joint Admission and Matriculation Board as equivalent to the SSC.

The advanced program requires two years of pre-entry industrial work experience and one year of full-time study in addition to the NTT/NCC. All certificates are awarded by the National Business and Technical Examinations Board (NABTEB).

Another type of – relatively new – vocational training institution is the so-called “Vocational Enterprise Institutions” (VEIs) and “Innovation Enterprise Institutions” (IEIs), established to provide employment-geared education in the private sector. At the secondary level, VEIs offer programs for graduates of junior secondary school leading to a National Vocational Certificate (NVC). Programs are between one and three years in length and conclude with the award of the NVC Part 1, Part 2 and Final.

At the post-secondary level, IEIs offer diploma programs for holders of the SSC. Programs are two years in length (3-4 years part-time) and lead to the so-called National Innovation Diploma. As of 2017, there were 137 approved IIEs and 72 approved VEIs listed on the website of the National Board for Technical Education.

University Admissions

Until the 1970s, Nigerian universities set their own admissions standards. Due to the growing number of universities in Nigeria’s sprawling higher education system, this practice became problematic, and, in 1978, the Nigerian government established the Joint Admissions and Matriculation Board (JAMB) to oversee a centralized admissions test called the Unified Tertiary Matriculation Examinations (UTME). The fiscal crisis of the Nigerian government has recently led to discussions about abolishing the JAMB as a cost-cutting measure. In November of 2016, the JAMB announced that it did no longer have adequate funds to effectively conduct the nation-wide UTME. Despite these financial difficulties, all public universities are presently mandated to use the governmental admissions test in their admissions decisions, even though some universities have additional requirements going beyond the UTME.

The Unified Tertiary Matriculation Examination (UTME) is a computerized standard test. The multiple-choice test is three hours in duration and conducted once a year, typically in March. It can be taken at test centers in each state of the Nigerian federation, as well as some overseas testing facilities.

The UTME is open to students who achieve credit level or better in English and four other subjects in the SSC exams at the end of the senior secondary cycle. Students with equivalent qualifications like the National Technical Certificate may also be admitted.

Students who sit for the UTME must take exams in English and three subjects related to their intended major in order to be considered for admission into universities. A total of 23 different UTME subject combinations are offered in the fields of: Banking and finance, law, English and literary studies, mass communication, linguistics, philosophy, engineering, medicine and surgery, computer science, nursing, pharmacy, biochemistry, industrial chemistry, geology, mathematics, microbiology, economics, sociology, psychology, political science, public administration, and accounting and business administration.

Test takers can achieve a maximum score of 400. Most universities require a minimum score between 180 and 200, although high-demand universities or programs may require higher scores.

Many universities also conduct additional screening or post-UTME examinations before a final admission decision is made. These post-UTME requirements can be demanding and are often reported to be a source of frustration for Nigeria’s university applicants. In 2016, the JAMB announced a number of reforms, including stopping universities from using written post-UTME exams, as well as changes to the UTME scoring system. As of February 2017, the status of the reforms was unclear, due to resistance from universities. Many universities continued to use post-UTME exams in the fall 2016 admissions cycle.

When registering with JAMB for the UTME, each student can apply to up to six institutions: two universities, two polytechnics, and two colleges of education, with first and second choice programs for each institution type. A number of universities accept applications for post-UTME admissions screening from students that that did not get into their universities of choice. Some private institutions accept applicants that did not sit for the UTME at all.

Not Enough University Seats

According to the statistics JAMB provides on its website, a total of 1.579,027 students sat for the UTME exam in 2016. 69.6 percent of university applications were made to federal universities, 27.5 percent to state universities, and less than 1 percent to private universities. The number of applicants currently exceeds the number of available university seats by a ratio of two to one. In 2015, only 415.500 out of 1.428,379 applicants were admitted to a university, according to the data provided by JAMB.

This admission ratio, low as it may be, is a significant improvement versus 10 years ago when the ratio was closer to one in ten for university entry. But the admissions crisis continues to be one of Nigeria’s biggest challenges in higher education, especially given the strong growth of its youth population. Nigeria’s system of education presently leaves over a million qualified college-age Nigerians without access to postsecondary education on an annual basis.

High unemployment among university graduates is also a major problem but does not appear to be a deterrent to those seeking admission into institutions of higher learning. In 2016, the online magazine Quartz reported that a staggering 47 percent of Nigerian university graduates were without employment, based on a survey of 90,000 Nigerians.

TERTIARY EDUCATION: AN OVERVIEW

UNIVERSITIES

The National University Commission (NUC), the government umbrella organization that oversees the administration of higher education in Nigeria, listed 4o federal universities, 44 state universities, and 68 private universities as accredited degree-granting institutions on its website as of 2017.

Many of these institutions are relatively new. In response to demographic pressures, Nigeria’s higher education sector expanded over a relatively short period. In 1948, there was only one university-level institution in the country, the University College of Ibadan, which was originally an affiliate of the University of London. By 1962, the number of federal universities had increased to five: the University of Ibadan, the University of Ife, the University of Nigeria, Ahmadu Bello University, and the University of Lagos.

Between 1980 and 2017, the number of recognized universities has grown tenfold from 16 to 152, as reported by Nigeria’s National Universities Commission.[6]For the first few decades of growth, higher education capacity building was primarily in the public sector, driven by Federal and State governments. More dramatic growth occurred beginning in the late 1990s when the Nigerian government began to encourage the establishment of private universities. Since then, private institutions, which constitute some 45 percent of all Nigerian universities as of 2017, have proliferated at a rapid pace, from 3 in 1999 to 68 in 2017. About two-thirds of these institutions are estimated to be religiously affiliated schools. Despite the sheer number of private institutions that have opened, enrollments seem to be relatively low. Although estimates are difficult to find, the small number of United Tertiary Matriculation Examination (UTME) applications to private universities indicate that private universities account for only a small percentage of Nigeria’s total tertiary enrollment, which UIS reported as 1,513, 371 as of 2011.[7] Covenant University, Nigeria’s largest private university reportedly had a total enrollment of 6,822 students in 2010/2011.

Nigeria’s 40 federal universities, as well as dozens of teaching hospitals and colleges, are under the direct purview of the NUC. State governments have responsibility for the administration and financing of the 44 state universities.

In addition to granting institutional accreditation, the NUC approves and accredits all university programs. Accreditation is granted for an initial three-year period and subsequent five-year periods. (For a detailed overview of the process see the NUCs 2012 accreditation manual). The suspension of accreditation for programs is not uncommon. In 2016, for example, the NUC publicized a list of 150 unaccredited degree programs at 37 universities.

COLLEGES AND POLYTECHNICS

In addition to universities, there are a large number of polytechnics and colleges under the purview of the National Board of Technical Education (NBTE), the federal government body tasked with overseeing technical and vocational education. In 2017, the NBTE recognized 107 polytechnics, 27 monotechnics, and 220 colleges in various specific disciplines. These institutions were established to train students for technical and mid-level employment.

The National Commission for Colleges of Education is the federal body dedicated to overseeing non-university teacher education. As of 2017, there were 84 teacher training colleges in Nigeria.

culled from: wes.org